|

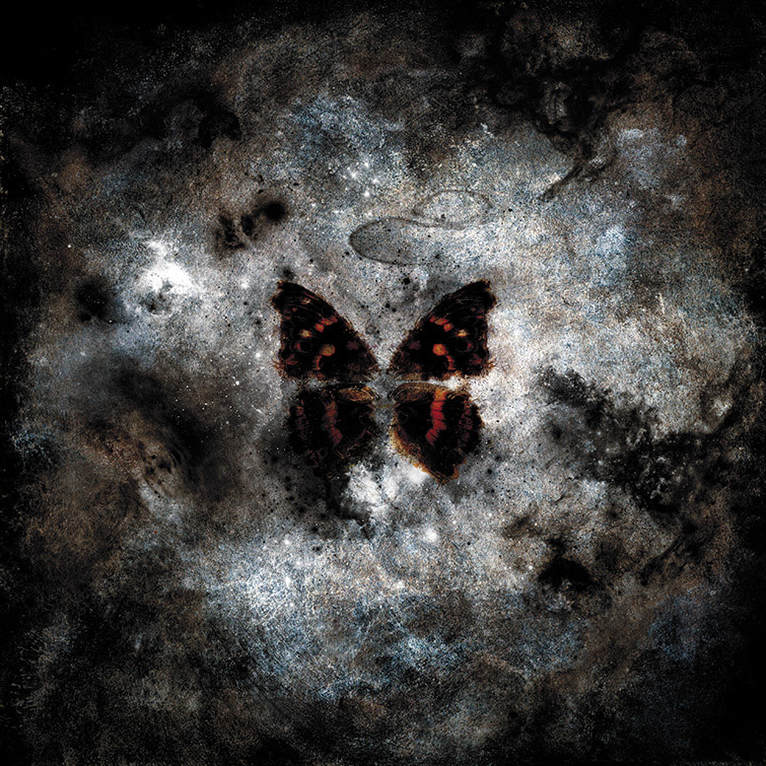

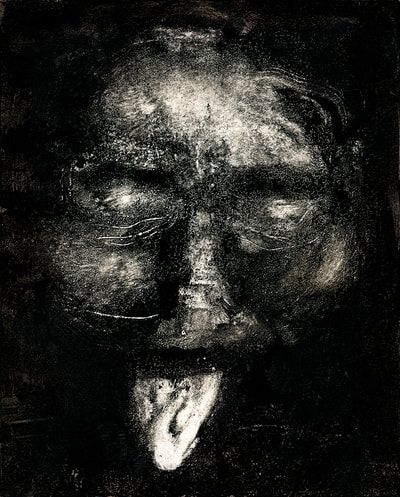

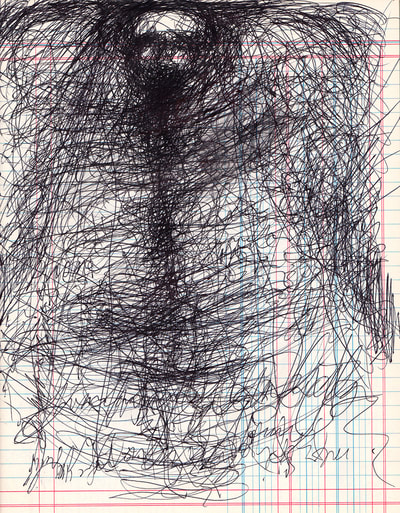

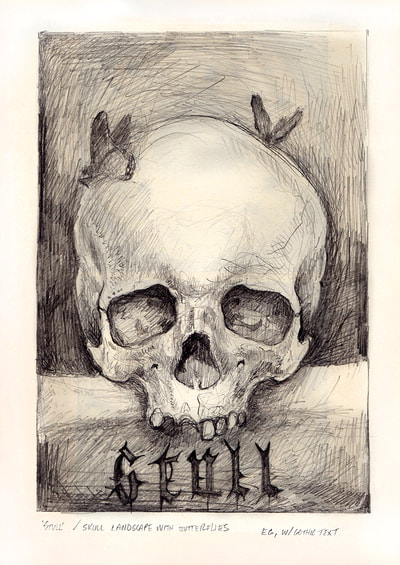

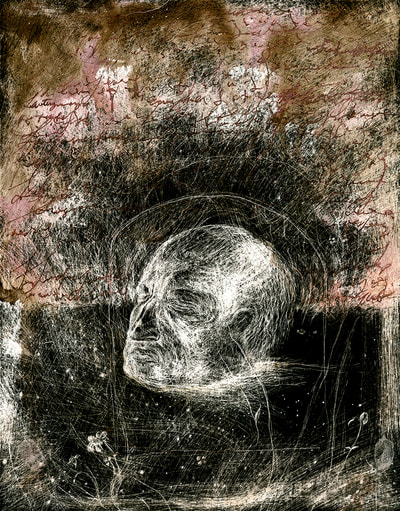

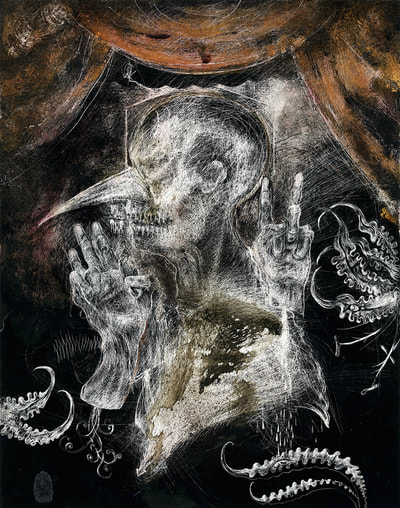

The work of Stephen Kasner is that of an artist exploring a realm of terra incognita most artists, whether out of fear or inability, never come close to charting. His subjects often find themselves cast as both catalyst and muse amidst a barren backdrop of existential longing. That, however, is not to say that the work itself is barren, and in fact quite the opposite is true. These paintings boil and writhe in the subtlest of ways that can be instinctually understood, but never fully articulated. This is an artist who finds his subjects in the darkest recesses of both the conscious and unconscious mind and presents them to the viewer in all their fallible and tormented glory. Ultimately there is a sense of hope within these walls of stretched canvas and paint. These figures may forever fight to keep the impending, inky darkness at bay, but they never fail to stave it off. Atmospherically speaking, the canvases often seem to be born of an ephemeral darkness. The figures in these paintings appear to have been scratched, scumbled, drawn, and painted into existence, yet, they are much more. They are as alive and as tangible as shadows, and as the beings that cast them. For all their sense of a textured, painterly roughness, of having been thoroughly worked, they resonate a certain polished elegance. It is an assured and granite elegance, much akin to that of marble. The way it tells us its story in the cracks, fractures, and fissures it displays beneath its smooth, elegant surface. These canvases seem to be born of a subterranean shadow world, yet the figures themselves exude an agonized illumination. This is often further intensified, not just by the darkness whirling about his subjects like angry locusts, but how he reminds us through his work that we are all surrounded by a darkness of the same fashion. As the illumination of a lantern in a dark forest often does, the light afforded one sometimes reveals more questions than answers. Indeed, the whole of his output consists of multi layered cacophonies of sustained brilliance and applied intensity. It is art fulfilling its full potential; these works have implications of a very complex and innate philosophical nature. There is no doubt that Stephen Kasner is an accomplished and technically adept painter and master visual artist, yet he has in more recent years extended the reach of his artistic vision past the confines of visual art. He authored Stephen Kasner: Works 1993-2006; an anthology of the drawings, paintings, and mixed media works that made his name. He is also the driving force behind the experimental music of Blood Fountains. We will be delving into that area of his output in our exclusive interview, as well in the latter part of this feature. With three never before heard tracks; one from Blood Fountains (Which you can get as a 10” silver/gold vinyl LP, included in the upcoming 2018 release of Stephen Kasner: Works, signed & numbered limited-edition book sets), as well as two exclusive, previously unreleased tracks from ArorA, and the original film from Blood Fountains, Moving Mountain, filmed in Belgium by Dwid Hellion, Tine Guns & Mathieu Vandekerckhove. We are very proud and honored to present to you our April Spotlight artist of 2018: Stephen Kasner. Stephen Kasner : Spotlight Interview With Steven Lee Matz Stephen, I would like to begin by exploring where art entered your early life. As a young person, were you always pulled towards art, or was there a singular moment when you realized art-making was what you wanted to do seriously or professionally? Drawing, painting, art making—these are practices I never thought much about, or was a path where decision played any role. Navigating my way through childhood with drawing; that wasn’t a thing I ever considered choosing. It was always there, and easily accessible. An impetus to create imagery was simply a natural extension of my mind, my thoughts, and it was a language I could understand. As far back as I can recall, there always existed a sort of pilot light within that was ever-present. Drawing and image making was my instantaneous, automatic, and even unconscious way to bring into existence those things that I wanted to see and understand, but was otherwise unable. It was a spontaneous tool to translate and define a language unknown to me, and it’s still very much that same way now. Who were and are your primary artistic influences? The main inspirational sources that have remained constant and infinitely resonant throughout my adult work as a painter include Francis Bacon and Austin Spare, Franz Von Stuck, Ivan Albright, Ross Bleckner, Fritz Scholder, Alfred Kubin, Anselm Kiefer, Odd Nerdrum, all of whom are generally or immediately contemporary. Though as is most healthy for any creative expressionist, I always openly seek to find inspiration everywhere, especially outside the traditional art world. Often, one can receive the strongest impressions and inspirations from things not at all connected to your own direct path. Naturally, music is a major driving force, both personally, emotionally, and through my work itself. But biographical stories also encourage me immensely, and plants, flowers, animals, and my own personal, individual relationships, are all sources of untold energies. Anything that holds clues or transmits reflections to the elusive mysteries of love and death are key. You can potentially find that anywhere. The world is full of countless signs and fleeting glances into the really great mysteries. That stuff is always right in front of you. You only need the soul to see them with. In addition to all of your output as a visual artist you are also the elemental force behind the music of Blood Fountains. How did that project come about and what is the philosophy behind it? Gravitating to a natural course through drawing, I also pursued the study of music. Of course, that pursuit took a bit more doing, as one needs a supportive parent to assist in the nurturing of something like that when you’re only 8 years old. But I did have supportive parents, and I suspect that it came as no surprise, nor was it confusing to them that I had that sort of interest. I didn’t have to convince them of my sincerity, or my intent to stay serious about a dedication to studying music. They had been witnessing the same driving behavior I had towards my art for some time by that point. I began to study guitar, and then electric organ and drum lessons at home followed. I’m acutely aware of the fact that there was a period of time, whether I chose it or not, that a deeper search through drawing and painting took the lead, and the visual side eclipsed the music study. Any of my friends who I’ve played and recorded music with all attest to this as well, with little doubt. It’s a strange thing; during that timeline when I began to paint seriously, the great bulk of my knowledge of reading and playing music—playing formally—just disappeared from my abilities. When I returned to playing music, I found myself with great, unexpected challenges of relearning everything I may have properly absorbed through formal study. From the time after that, when I decided to channel a combination of my own music and my art into one entity, I’ve no choice but to play and record with a similar set of psychological tools I use in painting. After years of initial frustration, I’ve come to not only accept what I considered limitations, but embrace them as an essential format in musical expression. I’m more pleased now, currently, as it feels more inevitable. I’ve accepted my limitations as somehow necessary to braid and weave my painting and music, and it’s through that same inevitability that Blood Fountains was created. Dwid Hellion was an early co-collaborator in your exploration and recording of experimental music. How did your connection together occur? I first met Dwid in 1997 while his band, Integrity, were just preparing to record their album Seasons in the Size of Days. Dwid had just seen my first solo gallery exhibition that was occurring at that same time. He got my number and called me, and after we spoke for several hours about music, art, religion, serial killers; he also laid out the concepts within the Seasons album. Dwid requested I produce the paintings for that album, which of course I was very pleased to accept. We always remained close, and our bond grew to explore some experiments in sound, initially through his ongoing Psywarfare project. Throughout 1997-99, I spent most entire weekends at his home recording with him. It was through his mediumship that allowed me to begin to explore a more serious level of my own ideas and concepts of what I felt was the natural ambition of my music. Refocusing the intent to translate the aesthetics, dynamics and emotions in what I was doing with painting, but through sound. How would you describe the creative dynamic between the two of you? Dwid and I have a great deal in common artistically, aesthetically, philosophically and intentionally. We understand each other intuitively, which is among the rarest of things. Dwid and I became instantly bonded through our immediate talks. We have remained trusted friends and collaborators for decades now, sharing a unique series of odd interests, examining the world as extreme outsiders. We both recognize our displacement in the modern world, we mutually accept it, and have both embraced that position long ago, separately but in tandem. There’s radical sources of power generated through these types of connections. Just like everything else, the level and quality of frequencies dictates the output. You mentioned the experimenting and recording of your music with Dwid, but that work together was not your first recordings, nor the beginning of your music that eventually became Blood Fountains. You were previously experimenting with sound as a project under the name ArorA? ArorA was the first legitimate series of attempts to document and record the hazy concept of what all my music is really about—to give some tangible form to a pure emotional target. You could call the music soundtracks to my paintings. That is essentially what the music is in the end, but the approach, premeditation, analysis, and production are far more complex than simply this. Ultimately, and hopefully, the music can be enjoyed by someone who has no idea about any of these intended connections, and not a clue of the parallel intent between the music and artworks, and just simply enjoy them as sounds or songs or whatever you might call them. And was ArorA an actual band, or how would you describe it? ArorA existed for perhaps a solid year of strictly recording improvisational experiments, guided only by a discussion of the means I mentioned, and an emotional focus, crystal clear, vague or abstract, was irrelevant in the larger scope of the almost ritual style between myself and Shawn Bateman, who was my sole collaborator in ArorA. I’ve known Shawn for most of my life. We are very much alike in a spirit-core way, in that we both scrupulously examine and define the world around us giving emotions a formal value. Emotions, what one feels within, has definitive weight and density and energy, and Shawn and I have always shared that core belief. It’s more than a belief, really. It’s a determination to the concept that emotions are a tool of measurement, and we all, consciously or unconsciously, use them all day, every day, to assess every moment in which we each exist, defining a perpetual value. Shawn is an extremely talented and natural musician, far more so than I am. There is never any comparison to our levels of playing. Shawn is cognizant and in control of his notes. I am not, but somehow that’s what works. After some time away, we played together again recently as Blood Fountains. Beyond his musicianship, Shawn is a remarkable painter as well. He as been a close friend and inspiration for many years. Your work was featured in the recent film, The Devil’s Candy, and is somewhat central to its entire concept. How did that project come about and what was the extent of your involvement in the production aside from the paintings themselves? Snoot Films, the production company for The Devil’s Candy, contacted me on behalf of Sean Byrne, who wrote and directed the film. As Sean explained to me in our first conversation, throughout his process of writing the story, he had envisioned my work as the precise imagery he wanted the main character, who is a painter in the story, to produce. The paintings of that character fluctuate, and are rather trapped in a psychological and spiritual battle. As the story unfolds and gets more absorbed in the mystery of the Satanic force that influences him, his paintings succumb to more and more demonic distortion. I was involved in every level of these creations as essentially the painting-maker behind the paintings we see as the work of the main character. My production of the paintings took place privately, well in advance, and continuing during the shooting of the film. I was not on the set during filming, and due to the unbelievably stressful time constraints to produce the large number of works necessary to the story, I continued painting up to and during filming, while communicating with Byrne. There were over 25 individual pieces of varying sizes and stages required for the film, which I completed in approximately seven months prior to shooting. It was really an impossible task, well beyond daunting, and I reminded Sean of that every chance I had, I’m sure. You and I previously discussed the work of HR Giger, with whom you had known personally. Can you tell us a bit about that friendship and how it affected your path as an artist? I would never be so bold as to define my association with Giger as friendship. That’s HR Giger. Frankly, I still have a very difficult time wrapping my mind around the fact that I ever had the privilege of meeting and knowing him at all. There’s also the psychological wall that exists due to the fact that, undoubtedly, Giger has always been one of my greatest influences. I was barely in my teens when I discovered his work in Omni Magazine. Those experiences, seeing his paintings in print, were startling enough where it wasn’t even a part of the equation to consider them paintings. He was creating another world out of nothing and nowhere. If you are a person who truly understands and revels in Giger’s work, you will know that there are no words to describe it. What I know is, I was invited to visit his home, I was there, and the facts blur at that point. That experience is not something one can keep in words or expressions of any kind. It is instead, something you can only hold within your heart, and you guard it under lock & key. I will continue to do that for as long as I am in a human body. As a painter you have a distinct, original style, which is unmistakably your own. By what process are one of your paintings born, both conceptually and technically? I expect as much as any artist, painter, musician, or anyone who evokes personal creations, this is a difficult thing to express or explain. It sounds peculiar, I’m sure, but sometimes even I am not so sure how these things come into being. I think the element of style occurs as a by-product or side effect of this personal creativity that, at its finest, remains subconscious. If at any time an artist becomes conscious or aware of the concept of their own style, you’re in trouble. That is when the danger of forced creativity is in play, and you are very potentially doomed to some sort of failure, either within the moment, or in a particular piece, or worse. Also, every artist has their own personal goals; radically varying levels of what one hopes to achieve. Some only seek to explore marginal, surface things, and others go deeper. Some, as you mentioned Giger, channel revelations pulled from some bottomless pit that is clearly not of this world. My work is exceedingly personal and subconscious, and I am indeed only interested in pulling from depths previously unknown to me. The reaches I take don’t have to be radically far. Very often, I pull from parallel-universe locations that can be right next to me. One only needs to know how to reach in. This action, and how I achieve it, is a kind of ritualistic event I have practiced and cultivated with my work for many years now. It’s rather like imagining yourself in a trance, or in mid-hypnosis. When you’re in it, right inside it, that’s one thing; but when you return from it, it’s often a remarkably difficult, if not impossible state of reality to put into words, or analyze, or sometimes even understand. As an artist, especially a visual person, a painter, attempting to reveal the things I do, you have to very often simply not attempt to understand it. It can be a counterproductive method to spend energy dissecting and comprehending the how and why the channeling of these things actually happen. The fact that they do, and one is able to access certain unconscious levels of being, and even invisible states or however you prefer to acknowledge it, is a blessing and a precious magical thing. It just is, and that’s all there is to it. Tracks 1 and 2: ArorA, Psychedelic Solutions [Unreleased Improvisation Sessions, 1996] All instruments and sounds: Stephen Kasner & Shawn Bateman. Track 3: Blood Fountains, Blood Fountain All instruments by Stephen Kasner, David Beaver, & Daniel Koja Mastered by James Plotkin Exclusive track from 10” silver/gold vinyl LP, included in the upcoming 2018 release of Stephen Kasner: WORKS, signed & numbered limited edition book sets. Blood Fountains Moving Mountain. All instruments by Stephen Kasner Filmed in Belgium by Dwid Hellion, Tine Guns & Mathieu Vandekerckhove Mastered by James Plotkin  Self-Portrait. Polaroid, acetone, mixed-media, 6X6 inches, 2018. Self-Portrait. Polaroid, acetone, mixed-media, 6X6 inches, 2018. Stephen Kasner Stephen Kasner’s paintings, drawings and photographs have been exhibited and published worldwide. Gallery exhibitions of his works have been hosted in Chicago, Los Angeles, San Francisco, New York, among many others, as well as in Europe and throughout Australia as part of the internationally renowned Collection Art Visionary. His paintings and mixed-media works have been published to accompany numerous articles and editorials of vast social spectrums. Kasner is also widely recognized as a singularly masterful visual interpreter of music, producing a remarkable number of his unique images to accompany record albums for such modern musical luminaries as SubArachnoid Space, SUNN 0))), Darsombra, Khlyst, Suma, Justin Broadrick/Final, Skullflower, and Aluk Todolo, among many others. Stephen continues to collaborate as visual artist for a series of bands and musicians, creating original artworks for upcoming releases by Suma and Istvan Megdyesi, and has recently produced a series of unique automatic drawings for The New Recordist, an upcoming release from German experimental electronic musician, Marc Lansley. Kasner is currently working exclusively with Dark Art & Craft, producing an ongoing series of limited edition prints, as well as producing new original works for upcoming Australian tours of Damian Michaels’ Collection Art Visionary. Stephen Kasner is represented by Paul Calendrillo Gallery, New York: www.paulcalendrillo.com Limited edition fine art prints available exclusively through Dark Art & Craft: www.darkartandcraft.com/stephen-kasner

1 Comment

|

A great specter is looming over the art world: the specter of Inter|Sekt. For far too long we have watched the artists of our generation turned into a disposable commodity, bought and sold by the galleries, stifled in their expression by the tastes of the art consultants who purchase pieces on behalf of financially minded clients who want a "solid investment".

They have been amalgamated into schools, said schools are a device of gallerists and art historians to divide and conquer the creatives and free thinkers. For we live in a nation which thinks itself to be free yet is not, they expect the same of their artists. Our culture has been raped and plundered by the upper echelon, picked apart and sold by the same greed mongers who claim to be it's patrons. The tool which has most effectively stunted the growth of modern American art in particular is the clever indoctrination of this idea of schools to not only the art student but anyone whom even reads a brief survey of the history of art sees that it is broken up into these categorized schools; the philosophies of these various sects creates conflict, division, and ultimately destruction of the morale and submission to the established order. Thus rendering the creative spirit confused and useless. This helps curb the rebellious spirit of the average citizen outside of the art world in other spheres of society. Art history is a lie and galleries are dens of thieves! Inter|Sekt is not destroying the schools or the galleries, we are simply showing you they were never real, at least not in a world outside of that constructed by academics to sell text books to art students. The reign of the gallerists and art consultants is over when you want it to be. From the ashes of the indoctrinated schools of every form of art shall arise The New World Creative. -Steven Lee Matz- The inter|sekt manifesto

CategoriesStaff

Jim Mazzocco Archives

September 2021

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed